Kaori Lau and Tracy Humphries gave an excellent guest lecture on the importance of inclusive technologies in the classroom.

One of their main points included the importance of not modifying the curriculum for all students who have learning needs. A common misrepresentation of these students is that they need to have separate assignments or separate learning goals in order to succeed.

Rather, as the guest speakers highlighted, most students with, or in the process of attaining, Individualized Education Plans (IEPs) are fully able to meet standard curricular outcomes. However, the means that they can traditionally represent their learning, or engage with classroom materials, are restrictive.

For example, if a student with dyslexia was tasked with reading a short article and writing- by hand- a paragraph response, they would likely struggle with the assignment. It’s not that the student can’t do it. It’s that their ability to access the material and show their learning are restricted.

As a result, students feel isolated in the classroom. Because they may struggle with traditional means of learning and representation, students feel they are behind their peers in achievement. These effects are not just reflected in academic scores, but also negatively impact student’s perception of self as a capable and intelligent individual, as our speaker’s mentioned.

As an English and Social Studies teacher, my subject’s traditional means of learning have been the textbook and essay response. While fantastic leaps have been made in revamping the curriculum and content brought into the subject, the subject focuses on regular focused instruction (teacher goes up to the front and presents) and written work.

For a student with ADHD, sitting in the classroom while the teacher presents may be difficult to engage with. Without clear time stamps on classroom activities, the focused instruction may seem to unduly stretch on without a clear ending.

Just Five Minutes More!

In Michael’s list of assistive technologies (linked here), he mentions the use of a timer in the classroom. While it’s a simple addition, I’ve found it useful in my own explorations into teaching.

For my first few lessons, time became very subjective to me. I thought that my focused instruction had only taken 5 minutes, but when I checked my watch, I found that 10 or more had passed by.

It was like being in an X-Files episode where a character experiences time differently from other characters.

Except in my case it was just me losing track of time, and students struggling to stay awake.

I found setting a timer for 15 minutes (aiming for a total of 20 minutes) helped both to keep me on track, and students from falling asleep.

I use a Timex Ironman, which has a persistent and loud timer. When it goes off, students know that I’ve set five more minutes to wrap up focused instruction, and move onto the next part of class.

Doing this, students can hear that the end of focused instruct is coming soon. This helps to give clear timelines to students who may struggle with more passive modes of instruction.

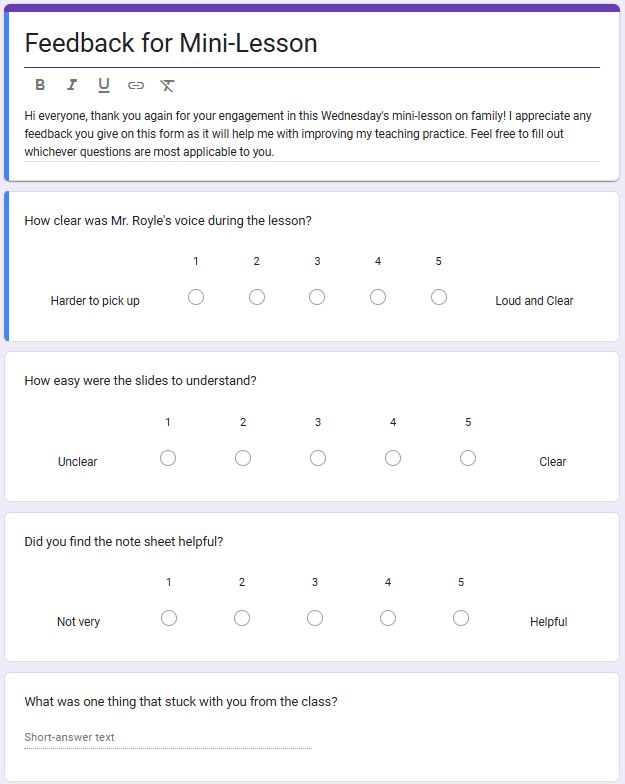

Another technology that may be helpful for some students is speech-to-text. I experimented with two dictate functions, one on Microsoft Word and the other on Google Docs.

I found Word’s dictate function to be easy to use, needing only my computer microphone. While it was mostly accurate in copying down my voice, I found I had to speak especially slow and clearly for it to work well.

I have included a screen snippet of my sample text below.

I wonder if the artificially slow pace Word’s dictate needs would be a barrier to some students. When I dictated, I found it hard to keep track of my thoughts while pacing out each word.

Google Doc’s dictate function was easier to use. I’ve included my sample below in quotes.

“Does this work? this software seems to work better than Microsoft Word. it’s more naturally used and it picks up my voice easier so far so good.”

I especially liked how I could state “period” or “delete” into Docs, and it would perform that function. I also found I could speak more naturally with this software as less typos were picked up.

As Google Docs is more prevalent in the classroom, and freely accessible to students at home, I would lean towards using Doc’s dictate over Word’s. Although I can see how it’d be difficult to dictate in a classroom setting, I would still recommend this feature to students.